Physical Education Teacher in Singapore

Twitter: @ReinventTheGame

Email: [email protected]

Blog: Reinventing the Game.... https://reinventingthegame.wordpress.com/

Taken from Reinventing the Game... by request of the author

Reinventing The Game (RtG) is about creating that environment of ‘reinvention’ for the students as they explore the Playability of games while they embark on the understanding journey to learning games.

In RtG, I explore ideas of Technical Concepts and Tactical Concepts. I look at games as a complex system and the solutions to solving problems in games (ie. learning in games) requiring complex system adaptation. Excellent work has been done in this areas by many and I find that pulling it all together is the work of us teachers. I once attended an international conference and sat in 3 concurrent sessions on learning. One was from a neuroscience perspective, the other from a cognitive learning specialist and the last from a pedagogy point of view. All 3 could have achieved more comprehensive pragmatic outcomes if they had come together to leverage on each other’s specialties when looking at the common point of how students learn. One of the big problem I see clearly (at least to me) is the lack of connection in research to the everyday on-goings of a classroom. Without doubt, the work done at the academia level does concerns the teacher and is vital information to lesson development in PE but I feel the need to also have good bottom-up initiatives from teachers on the ground to put together leanings from controlled environment research with their real day-to-day experience in a seemingly uncontrollable environment.

One belief I have is that even the best thought out theory needs a stamp of approval from its intended users. In our field, there are times that the seal of approval remains evasive, as we, the practitioners, are just too busy in our field to recognise the importance of being current in necessary knowledge. It is a tough battle that probably results in the theory-practise gap that we often talk about.

Recently, my professional learning network on social media (an ever-questioning Swedish professor!) pointed out the research area of phenomagraphy and the Variation Theory of Learning. Wright and Osman, (Wright & Osman, 2018) quoted Ference Marton (1981), describing phenomagraphy as a qualitative research specialisation which focused on “content-oriented and interpretative descriptions of the qualitatively different ways in which people perceive and understand their reality.” When compared to our more familiar constructivist paradigm, i.e. learners construct their knowledge from experience, phenomagraphy includes taking a step backward (or forward) to figure why the same content is understood differently, perhaps allowing us to understand social constructivism better. The concept of discernment and therefore being aware of a possible solution from a not as feasible one comes to mind. Therefore, discerning ability plays an important role in learning and it was disected further to explore what allows that better, i.e. through the Variation Theory of Learning. The paper being referenced here does not deal with Physical Education (PE) (the stretch to movement skill acquisition may or may not be significant possible) and is written from a social perspective that puts emphasis on the environment of the learner and not individual differences, which is enough for me put it to a PE context. It looks at the existence and meaning of awareness and thus possible learning.

Let me quote these lines from the Wright and Osman (2017) paper;

“According to Variation Theory the theory, a meaning always presupposes discernment and discernment presupposes variation (Marton & Pong, 2005). We can only discern a new meaning through the difference between meanings (Marton, 2015). “Every feature discerned corresponds to a certain dimension of variation in which the object is compared with other objects.” (Marton & Pong, 2005). Its central conjecture is that “meanings are acquired from experiencing differences against a background of sameness, rather than from experiencing sameness against a background of difference” (Marton & Pang, 2013). According to Marton (2015) “The secret of learning is to be found in the pattern of variation and invariance.” The pattern of variation and invariance in teaching does not guarantee learning but makes it possible. ”

The pattern variation and invariance mentioned above suggest that in order to learn, what is critical is first the ability to be aware that something needs to be learn via discernment in the learning design, i.e. what works well and what not so well in contrast. These discernment features are alternatives presented with activity design and does not support the fixed, one-solution learning activity where no alternatives are presented that allows for that discernment. This suggest an optimal learning environment that needs exploration of possible solutions in order for learning to be locked-in meaningfully. A simple outlier example given was that one could not understand colour if there was only one colour!

I am going to quote a few more lines from the paper again as it is very clear as it is;

The notion of the ‘object of learning’ is further specified by Pang and Marton (2005) as the 1) intended, 2) the enacted and 3) the lived object of learning. The intended object of learning, the capability that is intended for students to develop in relation to a subject matter content. The enacted object of learning refers to making the object of learning available to the students to learn in in the classroom. The lived object of learning refers to the ways in which the object appears to the learners.

The above screams to me our practitioner emphasis on the first two points and a big disregard or ignorance of the last point, the lived object of learning. Our teacher training and experience focuses a lot on being aware of what needs to be taught and presenting that to the students. Many of our formal structures in planning and evaluation are rather good in presenting this flow that is expected to allow learning. I call it the teacher input-student output flow of expected learning that may inadvertently ignore what happens between teaching cues and learning. While I use the word “between” which might suggest only teacher and learner variables, it is clear with the areas of expertise that I have been leveraging on for understanding that important information from context and internal processes comes together and even from further afield sometimes, i.e. social-cultural factors.

Quoting again;

Teaching involves making judgements of what is to be learnt, identifying the necessary conditions for learning and organizing educational practices to support learning. (Marton, Tsui et al., 2004). If teaching is truly focused on improving student learning towards expanded awareness of different aspects of reality, the teacher needs to understand what their students understand about the content about which they are learning. What is critical for teaching is thus not their general subject knowledge or pedagogical knowledge, teaching style, methods, skills or competences in general, but what they intend their students to learn, what they understand their students’ need to learn so that can develop their understanding of the object of learning and how they see teaching can help their students’ learning. This requires understanding of different ways in which students make sense of the content prior to, during and after teaching. Furthermore, it requires continuous assessment of the different ways in which the content is understood by the learners in relation to the aims and continuous revision of plans to further improve students learning. (Marton & Booth, 1997; Marton et al., 2004)

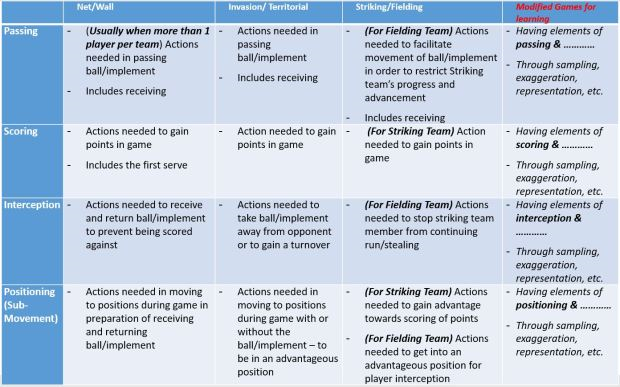

All these are the latest in my pursuit of understanding the context better for learning. Long ago I created a framework to help deliver teaching strategies for the teaching of games, Reinventing the Game (RTG). This framework looks at games from four perspectives; Passing, Scoring, Interception and Positioning (Replacing the original word Movement as I realised the incredible overarching significance of this word in the world of PE! – see Fig 1) – PSIP. These perspectives in its offering to students can represent rules and/or desired action-behaviour. Of course, this needs to be presented via effective pedagogy. The overarching initial desire for me to categorize all learning consistently and conveniently is to allow a familiarity of common themes between games for students in their learning and for teachers in their teaching. Over time, I find that such categorisation also allows a systematic planning and implementation framework as I discover and learn more in the field of teaching and learning, even after two decades of service. The realisation came later but I realised that RTG was also a personal philosophy of teaching where I grappled with understanding the seemingly simple elements of a game and what it takes to make games, as part of physical activities, a vital part of any learners’ life. It is about learning for understanding and creating enough ability in a learner that skills are always being generated as a mainstay of teaching as opposed to decomposing movement as primary.

Another perspective are the actual descriptors used in PSIP. They are words that equates easier in the typical vocabulary for a learner and thus understanding, when it comes to games. They are easy descriptors that can be built on for necessary complexity depending on learning stage. At the moment much of our learning in games are usually categorised into the terms defensive and offensive. For me, these usually results in a technical perspective that may not seem game-like as opposed to passing, scoring, interception or positioning. Of course, we still built up all learning to these two important elements, i.e. defensive and offensive. The other thing I notice is that any learning that involves at least two of the PSIP elements becomes game-like and representative, albeit modified, of an actual game situation. It also sorts of keeps me in-check when I spent too much time on single element activity, i.e. isolated unidimensional drills, and neglect adding a purpose for understanding for the skill being taught. E.g. while I try understand action-behaviours in terms of the four perspective above, I absolutely do not expect responses in the four areas separately to gauge learning. It might end up not being relevant and too far off authenticity to effect good leaning progression.

A key point here is that order and linearity in teacher thinking and planning does not represent the non-linearity and complexity of actual learning and thus movement in learners. I endeavour to use RtG to allow me to progressively plan for needed variability in solution exploration presented through carefully thought out relevant problem scenarios. Order within the disorder. While my learning design may involve minimum two of the four perspectives of PSIP, attempting relevancy to game context, the focus of learning for the activity can be just one of the areas.

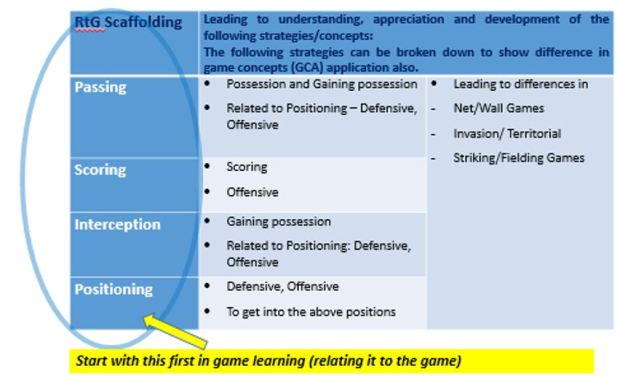

As I look deeper into concepts of affordances (what possibilities the context present to the learner), cognitive theories (traditional vs ecological/computational vs perception-action/indirect vs direct perception), social constructs in learning (learning for understanding via experience), etc., I realised that all these are part of the big picture and that a basic guiding framework helps in supporting implementation – see Fig 2. A framework is needed to help guide if you have a group of learners facing you for PE tomorrow, i.e.

- Where (where in a learner’s journey is something needed),

- What (what the learner needs at the above point in time),

- How (how we delivering what the learner needs) and

- Why (why is what we are doing effective and needed for the learner’s understanding).

Reference

Wright, E., & Osman, R. (2018). What is critical for transforming higher education? The transformative potential of pedagogical framework of phenomenography and variation theory of learning for higher education. JOURNAL OF HUMAN BEHAVIOR IN THE SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT, 28, 257 – 270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2017.1419898