Physical education teacher educator, educational designer and researcher in the School of Sport Studies at Fontys University of Applied Sciences.

Eindhoven, the Netherlands.

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @GwenWeeldenburg @TeachingGames

Facebook: Netwerk Teaching Games

LinkedIn: Gwen Weeldenburg

Website: www.netwerkteachinggames.nl

The model includes guidelines for the process of designing, teaching and assessing games. By following the various didactical components in the model, the PE teacher is able to create and manage a learning environment in which the learning process of the students (i.e. learners; players) will be facilitated, supported and monitored. However, given the complexity of the real (games) world, and the variety within contexts, conditions, psychomotor and affective skills of students, the model should be used flexibly rather than rigid. The main objectives of the GIM is to facilitate understanding, aid decision making and offer structure within the processes of designing and teaching games.

GIM is underpinned by theoretical frameworks with regard to motivation (i.e. self-determination theory; achievement goal theory), learning (constructivism; situated learning theory) and motor learning (dynamical systems theory; constraints-led approach).

Like TGfU and other game-based approaches, the GIA places the individual learner (i.e. player; student) at the centre of the learning process within a realistic context of a game or game form. Continuously creating an authentic and meaningful game learning environment for students is one of the basic principles. An environment in which students’ engagement and problem-solving is elicited by giving them autonomy and responsibility for their own learning process.

Games classification

To provide players with insights into the underlying structure and (tactical) principles of games, and thereby promote transfer of learning, the classification of games into Invasion, Net/Wall, Striking/Fielding and Target games is explicitly used in this approach.

Within the GIM these kind of game challenges with underlying success criteria and if-then principles form the starting point for the designing process. Based on a specific game challenge intended learning outcomes are determined. Outcomes on which relevant game learning and teaching activities can be designed and conducted, and the learning progress and outcomes can be assessed.

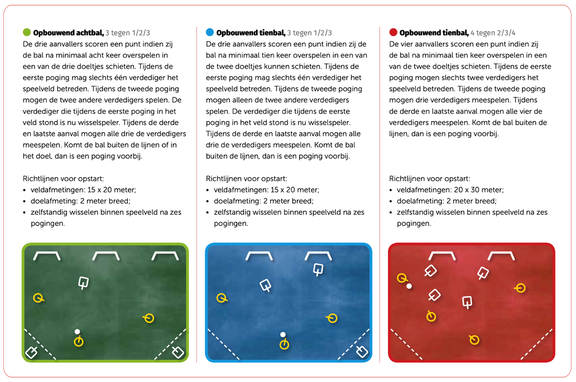

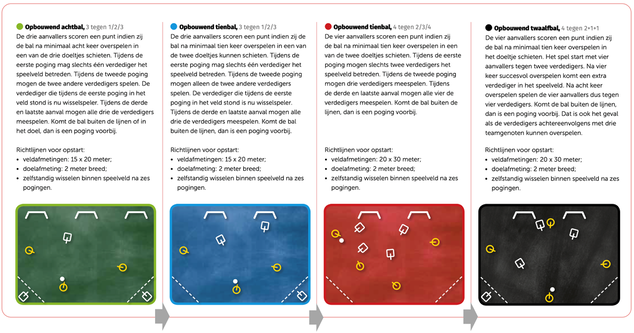

To optimise students’ learning it is important to provide students with game activities which are feasible, but at the same time challenging. Therefore, the psychomotor and affective differences between students should be considered. By utilising the metaphor of the green, blue, red and black ski slopes, the game learning activities in GIA are designed and presented in varying levels of complexity based on specific learning outcomes (see figure 2). The green game slope represents less complex activities than for example the red game slope activities. With that you can place students on different game slopes within the same class based on their skill level and abilities. For example, one group of students is learning skills with regard to maintaining possession of the ball (‘game challenge’) by shielding the ball from opponents by using the body (‘success criteria’) in a red game slope activity (e.g. 4 versus 4). While at the same time another group of students is involved and challenged in a green game slope activity (e.g. 3 versus 1).

Components of the Game Insight Model

To enable intentional learning, it is crucial to make the learning outcomes explicit at the beginning of the learning process. The learning outcomes provide students with a clear purpose (‘feed-up’) to focus their learning efforts. At the same time, these outcomes direct and guide your choice of instructional and assessment activities and strategies. In GIA the elaboration of the (authentic) game challenges and underlying success criteria and principles, form the basis for determine and describe the learning outcomes.

Optimise Engagement & Appreciation

After you have determined the (authentic and realistic) learning outcomes it is important that the students gain positive and meaningful learning experiences at the beginning of their learning process. Experiences that increase, or at least preserve, engagement in and appreciation for playing games. By placing the students directly at the beginning of the learning process in an authentic (green, blue or red) game form that matches their skill level, this could be achieved. A game form in which the students know what is expected of them, in which every student is of value and can be successful. But also, a game form in which the students frequently are being confronted with the game challenge you have selected and described as a learning outcome (e.g. ‘maintaining possession of the ball’ in invasion games).

After you have focused on students’ engagement in, and the appreciation for game play/ the game form, special attention should be devoted to optimising tactical skills. Skills which ensure students know what to do when and why in game situations. In the previous given example concerning ‘maintaining possession of the ball’ during invasion games, the attention in this phase of the learning process should be therefore focused primarily on designing and conducting game forms in which students learn what to do (i.e. ‘protect the ball by positioning your body between the ball and the opponent’), when (i.e. ‘if the opponent reach for the ball’) and why (i.e. maintaining possession of the ball, to continue the game and eventually attempt to score).

After you have optimised students’ engagement in, and appreciation for the game form, and provided students with (basic) tactical insights (what, when and why), in this phase of the learning process there could be an explicit attention for the development of technical skills. Reference is made here to ‘explicit’, given the fact that also in previous phases of the learning process the development of technical skills have (implicitly) occurred. In the GIA technical skills refer to the ability to perform a specific task or movement. It includes some qualitative aspect of both the mechanical efficiency of the movement and its relevance to the particular game situation.

With regard to game challenge ‘maintaining possession of the ball’ in this phase there could be (more or explicit) attention for the answer on the question ‘How?’. Therefore, the students are placed in a part practice game situation (e.g. 1 + 1 versus 1) in which there is a strong focus on how they can use their body in order to shield the ball and maintain possession of the ball. Technical skills in this example refers to the body movement, foot placement, keeping balance, controlling the ball, et cetera. However, based on the current insights of motor learning (i.e. dynamical systems theory; constraints-led approach) isolated skill drills in which the task or movement is disconnected from the results or particular game situation, must be prevented as much as possible. In addition, explicit rules and too much verbal instructions should be avoided as well.

In the GIM the PE teacher can also decide to skip this phase and proceed directly to the next phase. For example, when there is insufficient time available or the explicit need for technical skill improvement is missing.

Apply in (more) complex game form

In this phase of the learning process, the developed (tactical and technical) skills are being applied in a complex game form. Preferably a game form that is more complex than the game form that was applied at the start of the learning process (i.e. in ‘Optimise Engagement & Appreciation’). Therefore, a black game slope activity is added in this phase (see figure 5). Make sure that the complexity of the game form is perceived by students as a challenge rather than an obstacle. Therefore, you have to ensure the right balance between success (feasibility) and failure (challenging).

At the start of the learning process you determined the direction of student learning by describing and communicating the learning outcomes. In this you have taken the starting level of the students into account and selected learning outcomes which were feasible and challenging for every student. Based on these learning outcomes you systematically designed and managed a differentiated game learning environment.

In order to guide and support student learning properly, information on the learning progress and learning outcomes is needed. By employing assessment activities, the PE teacher can obtain this information. Through formative assessment activities (or ‘process feedback’; for an overview see Shute, 2008), the teacher is able to monitor student learning and identify strengths, weaknesses and difficulties that need work and help to address problems immediately during the learning process. To determine to what extent the learning outcomes have been achieved by students and your teaching has been effective, you will need summative assessment activities. Both assessment types (i.e. formative and summative) are essential in the context of PE. However, since feedback received within the learning process is more powerful for student learning than feedback received at the end of the learning period (Hattie & Timperley, 2007), the emphasis should be on employing formative assessment activities.

Create a motivational climate

The PE teacher faces the challenging task to provide students with competencies that enable and encourage them to participate in (game) activities in and outside the school setting. The PE teacher is however unable to enforce student learning and to determine which student learns what at what time. Consequently, the focus should be on creating the most favourable conditions in which student learning can take place. By systematically constructing a learning environment that meets the motivational needs of the student, a positive impact can be exerted on the motivation, well-being and therefore the learning process of the student. The motivational constructs (i.e. the psychological basic needs: autonomy, competence and relatedness) derived from the self-determination theory Deci & Ryan, 2000) and constructs (i.e. TARGET principles: Task, Authority, Recognition, Grouping, Evaluation and Time) from the achievement goal theory (Nicholls, 1984, 1989; Elliot & McGregor, 2001) are utilised in the GIA to create a motivational game learning climate.

For example, to become a successful game player, problem-solving and decision-making skills, among others, are crucial. According to GIA the PE teacher needs to employ teaching strategies for indirect instruction to promote the development of those (tactical) skills. Therefore, the use of questions and discussion are important strategies. By using (e.g.) the small-group discussion ‘think-pair-share’ method (teacher poses a question; students think individually; each student discusses her/his answer with a peer; students share their answers with the whole group) the students can be guided into discovering (new) ways of resolving a game (play) problem/ challenge. While at the same time these kinds of teaching strategies will satisfy students’ psychological need of autonomy and therefore promote student motivation.

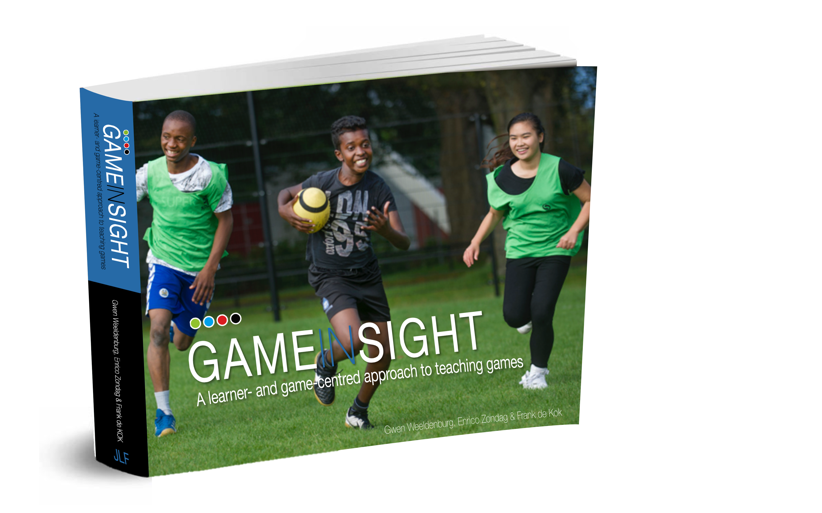

English Book Edition

If you are interested in this book, please let us know by sending us an email at [email protected].

Elliot, A. J., & McGregor, H. A. (2001). A 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(3), 501-519.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

Newell, K.M. (1986). Constraints on the development of coordination. In M.G. Wade & H. T. A. Whiting (Eds.), Motor development in children: Aspects of coordination and control (pp. 341-361). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Nicholls, J. G. (1984). Achievement motivation: Conceptions of ability, subjective experience, task choice, and performance. Psychological Review, 91(3), 328-346.

Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The competitive ethos and democratic education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78.

Shute, V. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78, 153–189.

Weeldenburg, G., Zondag, E., & de Kok, F. (2016). Spelinzicht: Een speler- en spelgecentreerde didactiek van spelsporten [Game Insight: A learner- and game-centred approach to teaching games]. Zeist, Nederland: Jan Luiting Fonds.