School of Physical Education and Sport Science, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece

Email: [email protected]

Research Gate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Aspasia_Dania/research

Google Scholar

Game-Based Approaches (GBAs) utilize pedagogies that bring back democratic and critical thinking principles within PE contexts. Within GBAs, teachers depart from rigidly scripted, individualized technique/skill practices to lessons that use modified games as relational spaces to promote students’ understanding. GBA teachers have to stay attentive during gameplay to gather insights about students’ needs and afterwards raise (tactical) problems to trigger personal reflection and group interaction. Afterwards, students use their game experience to collaboratively problem solve and develop individual and/or group strategies in consideration of game constraints and options. In terms of pedagogy, GBAs build on human dynamics and group effort to create learning environments that promote game efficacy and understanding in a manner that is equitable for all. As such, concepts such as tactical creativity, respectful interaction and shared thinking become the focus of the game experience promoting in this way students’ holistic learning.

However, elements like wonder, exploration and challenge cannot be experienced within games if the teacher does not have pedagogical content knowledge to tailor each game’s circumstances with contextual specificities (Gudmundsdottir & Shulman, 1987). The GBA teacher should be sensitive and knowledgeable enough to grapple with the ‘tensions’ of the game and use them as opportunities to (re)create conditions that will allow students to be, do, act and think different. From a socially constructivist lens, there can be no best-practice in GBA teaching since both game flow and student learning are the result of a complex network of interactions that cannot be easily predicted. It is important therefore that every teacher is familiar with the idea that GBA teaching is and should be a messy experience. An experience which is founded on the teacher’s ability to stay cognitively and affectively responsive to the game’s micro culture (e.g., structure, category, players’ abilities, etc.). For some teachers, this messiness might be felt as vulnerability and destabilization of authority.

Vulnerability is a misunderstood concept in education since it honors subjectivity and interrogation (Kelchtermans, 1996). According to Dewey (1929), if we expect teacher certainty as the absence of vulnerability, then we live in delusion. Vulnerability fosters empathy and divergent thinking and, if it not experienced as weakness, it may open teachers’ resistance towards instances of inequity within the lesson (e.g., in terms of game rules, scoring system, etc.). Within GBAs, teachers may experience messiness in their attempt to create learning environments in appreciation to students’ needs. This messiness is an indispensable part of good GBA pedagogy since it reshapes the teaching experience as production itself and not as a process for producing predetermined learning outcomes. GBA teachers learn from their trials to formulate game contexts that will help students to develop holistically as game players. When they fail to do so, two modes of action are open: (a) they may run away from ‘trouble’ and return to traditional teaching practices, or (b) they can set up efforts to modify the game with unsatisfactoriness being their experienced quality. In the second case, messiness becomes a condition of game-based teaching that is fundamental to teachers’ and students’ growth. All this experience familiarizes teachers with the idea that it is acceptable to feel vulnerable since it is impossible to know everything in terms of sensing and acting relationally to the complexity of the game. As such, teaching becomes professional learning since it helps teachers to confront their uncertainties or limitations and keep searching for different ways of caring for their students.

Based on the above, it is my convention that PE teachers should be supported to experience and implement GBA teaching as a messy process that nurtures students as whole human beings. Physical Education Teacher Education (PETE) programs should invest in GBAs and support future teachers to teach primarily for growth and secondarily for achieving learning outcomes. This means that future PE teachers should be encouraged to interrogate their established skills and habits with an emphasis placed on their critical capabilities. This may happen through their engagement with a variety of GBA courses, or within action research and lesson study projects. Overall, it is important that teachers understand that they are not trained to be technicians of game-based knowledge, but instead facilitators of student learning.

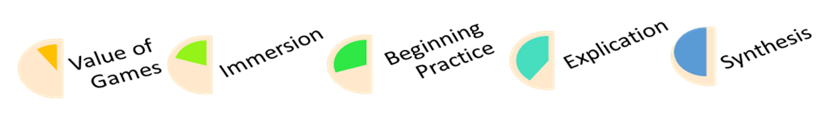

For this purpose, I suggest below the VIBES model (Figure 1), as a five-stage model for working with future PE teachers within game-based courses and PETE programs. The VIBES model is based on the premise that game-based teaching is a messy process of custom challenging for sustaining teachability and maximizing student growth. The five phases of the model are explained below:

(1) Value of games. Game-based teaching necessitates pedagogical content knowledge that is more than the application of game content or instructional skills. Thus, game-based courses should support teachers to reflect on their conceptions of what they understand as game-based teaching and what are its broader social implications and underlying values. Journal writing or narratives from their years as students or athletes in various sports could be used within the courses as a means of generating and supporting reflection.

(2) Immersion. As mentioned above, a deep exploration on the scope and philosophy of game-based pedagogies is needed to stimulate the teacher’s ability to teach in a human-centered way. Game based teaching is primarily a creative process since it promotes evaluation and reinterpretation of what is happening as action and interaction within the game. Thus, future teachers should be given multiple opportunities to share knowledge and understandings during the observation and design of game-based lessons. Learning communities (both face-to-face and digital), teacher blogs and forums could be especially set-up for this purpose, as part of PETE programs.

(3) Beginning to practice. After a period of theoretical sensitization, future teachers should attend practicum courses, in the form of short-terms placements in educational settings, to observe teaching and learning with GBAs in their authentic context. Field placements are also an excellent opportunity for future teachers to experience the messiness of game-based teaching ‘safely’ next to experienced PE teachers or coaches. Thus, mentoring programs (face-to-face and digital) could be a good start for supporting future teachers’ work in practicum

(4) Explication. During this stage, future teachers could experiment with making modifications to already scripted lesson plans. For example, teachers could be given a lesson plan designed under a sport-as-technique perspective and be asked to modify it by using GBA pedagogical principles (e.g., sampling, exaggeration, etc.). Afterwards, they could participate in course discussions with expert teachers or lesson study projects to analyze the outcomes of their work and get or give feedback.

(5) Synthesis. During this final stage, PE teachers may work in pairs and apply in practice their own game-based lessons. Peer feedback and reciprocal teaching may be used as means to this end. This process may be rather transformative for some teachers, since they will experience what it means to bounce off their reactions to problem solving to the reaction of their students. However, it is an exciting moment in enacting human-centered pedagogy as a process of both being and becoming a game-based teacher.

Dewey, J. (1929). The quest for certainty. New York: Minton, Balch & Company

Giroux, H. A. (2007). Violence, Katrina, and the biopolitics of disposability. Theory, Culture & Society, 24(7-8), 305-309.

Gudmundsdottir, S. & Shulman, L. 1987. Pedagogical content knowledge in social studies. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 31, 59‐70.

Kelchtermans, G. (1996). Teacher vulnerability: Understanding its moral and political roots. Cambridge Journal of Education, 26, 307-323.