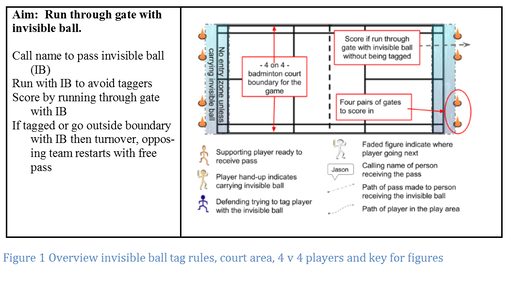

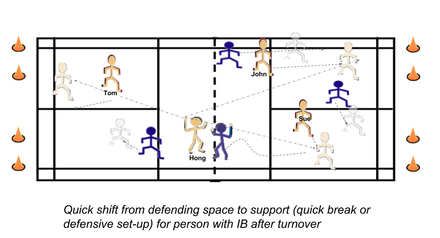

What if we taught the team play movement first before adding in the ball? What if we could get our students to realize how they work as team to support the person with the object to create time when needed, to create space in attack or deny space for an opponent? What if they could pass the object without having to practice their sending and receiving skills? The game in Figure 1 called “invisible ball tag” addresses these questions by eliminating the physical ball by using an invisible ball (IB). Figure 1 summarizes the set-up and basic rules to start the game with scoring happening when a player runs between the gates with the IB. This game exaggerates working on the synchronicity between players on a team with a similar effect on the opposing team. The IB is passed from one player to the next by the sender calling the name of the player and the receiving player acknowledging receipt of IB by raising their hand. The opposing team gets the IB by tagging the player with the raised hand.

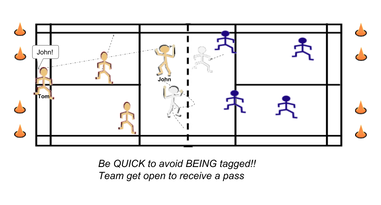

In Figure 2 a team of four players, John, Hong, Sue and Tom are playing invisible ball tag. Using the rules in Figure 1, John has his name called, he raises his hand to acknowledge he has the IB and runs to avoid being tagged. He then searches to see whom he could pass too. The self-organizing idea for the team with the IB is “Be quick, avoid being tagged.” Players on receivers team focus on “Get open to receive the IB.” The defending focus is to “tag the player with the IB” to get possession, but also “make sure you do not let the attacking team score”. At this point there is little synchronicity as players start to realize their role in trying to score or stop the opposing team from scoring.

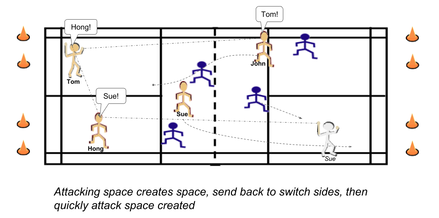

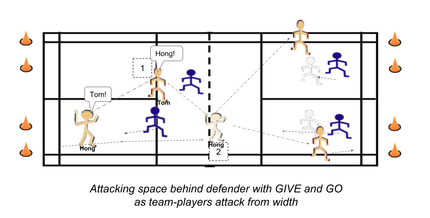

Figure 5 adds another possible synchronicity that builds on the previous two. From a teacher prompt such as “how can you attack the space behind a defender?” an attacking player with the IB can consider how to use their movement speed and quick passes. For example, as a defender moves to tag Hong who is moving forward with the IB, in order to avoid being tagged, Hong passes the IB to Tom but carries on running. Tom, sensing he might get tagged, sees that Hong is carrying on her run into space behind her defender so sends the IB back to Hong, creating the “1 - 2” pass or Give and Go.

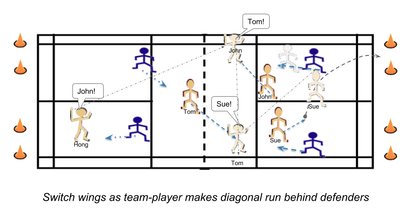

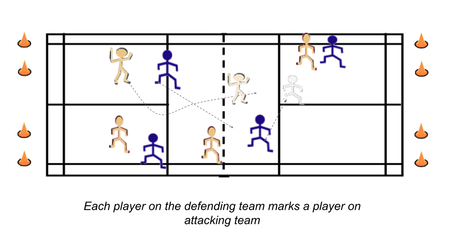

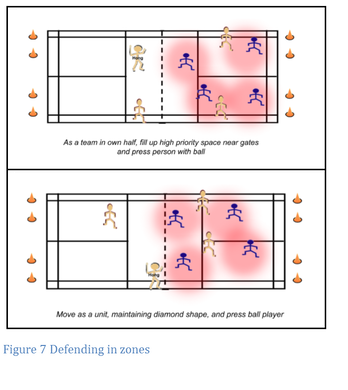

All these attacking interactions create a challenge for how to defend. A teacher could call a time-out and ask the teams to figure out how they can defend as a team. The next two examples suggest the type of defensive synchronicity that can emerge. Figure 6 presents the first defensive option where the defending team marks a player from the other team. This means the defending players shadow a player on the attacking team and if their player gets the IB then they try to tag the player without letting them get past them. However, if an attacking player does pass a player then another defending player needs to swap to pick up the free attacker; their beaten teammate then picking up the player they were making as indicated in Figure 6. The defending team works as a single unit focused on keeping gate side of the attacking players at all times.

Invisible ball tag draws on movement, as a form of literacy, communicating intent through movement to teammates. This form of human interpersonal synchrony and NCM, at its most basic level constitutes a communication network. This network has evolved over time to provide shortcuts in learning essential survival tasks. The game of invisible ball tag, played with an imaginary object, creates the ideal situation for players to see each other’s actions in the complex dance of attacking and defending the goals. This game allows the teacher to help the players learn to play as a team, to respond to their opponents working as a team, challenging players to adapt to their peers both on their own team and the opposing team. In this way players mimic, synchronize and co-evolve through the emerging interactions of the game.

References

Kauffman, S. (1997). At home in the universe: The search for the laws of self-organization and complexity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rhoades, J. L., & Hopper, T. F. (2018). Utilizing Student Socio-coordinated Mimicry: Complex Movement Conversations in Physical Education. Quest, 0(0), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2017.1373683

Thorpe, R., Bunker, D., & Almond, L. (1986). Rethinking games teaching. Loughborough: University of Technology, Loughborough.