PhD Researcher in Sports Coaching at Loughborough University & Former Premier League Academy Football Coach

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @ross_ensor

The approach I adopted was that of Game Sense (den Duyn, 1997) whose pedagogy is underpinned their theoretical tenets of Social Constructivism (Dewey, 1916/97) and Complex Learning Theory (Davis & Sumara, 2003) that learning is a social, complex, and interactive process. Underpinned by four key features for the coach to design…

- Designing a representative learning environment

- Emphasizing questioning to generate dialogue

- Providing opportunities for collaborative formulation, testing and evaluation of solutions

- Developing a supportive environment

Light (2013) contends that the coach must consider all four of these features when adopting a Game Sense approach, I will now articulate and provide examples of how I implemented these within practice when coaching youth academy football players in England.

Designing a representative learning environment

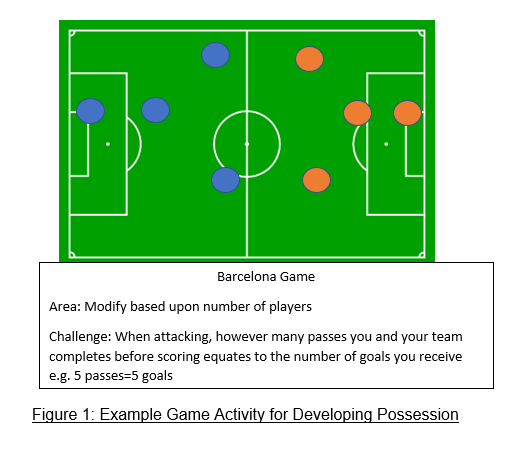

The Game Sense approach emphasizes that for all activities the coach should contextualize learning within ‘game or game type activities. In contrast to common taken for granted assumptions that technique must be developed first before playing a game. Although as Light (2013) contends this does not deny there is a place for ‘separate activities’ to develop skill and technique, however by placing too much of practice of context this may come at the expense of other areas such as decision making and tactical understanding. To design such activities, I adopted Launder (2001)’s concept of ‘designer games’ in which the game is modified to focus on specific aspects of the game within an activity. An example I adopted was aligning game challenges semantically to a team to add to the authenticity of such games for players. The example within Figure 1 is a game designed to encourage developing or retaining possession…

The implementation of questioning with Game Sense requires a repositioning of myself as a coach to a facilitator of learning as opposed to a director of it. The benefits of questioning are widely acknowledged in developing problem solving and promoting critical thinking. Additionally providing a reflective link between the social and cognitive areas of learning. For example, when a question is asked, we as coaches provide players with an opportunity to critically reflect on the activity by bringing to their ‘conscious’ mind there ‘unconscious actions’ to develop ‘understanding in action’ (Harvey & Light, 2015). This requires effective design by the coach to provide questions that provide evaluation and synthesis, acknowledging that questions should not limit the number of potential responses but expand them. To implement this within practice activities I used an adapter version of Kracl (2012)’s question starters for an activity of developing possession with overloads…

Coach: By using the ‘joker’ players what would this allow us to do?

Player: Keep the ball easier because we have an extra player

Coach: Okay, great so could the ‘joker’ players help us more?

Player: They could stand in space away from other players

Coach: Great answer, so if they’re in space how would it make the game harder for the other team?

Player: They would not know who to mark, or whether to come to the ball or not

Providing opportunities for collaborative formulation, testing and evaluation of solutions

At appropriate times within the activities as an extension of individual questioning I have implemented what Light (2013) conceptualises as ‘team talks’. This provides opportunities for players within their team to collectively formulate strategies to solve problems and then ‘test’ their effectiveness within the game. Furthermore, they can critically reflect upon whether their strategy was effective or not and why, to then potentially formulate alternate tactics and strategies. In accordance with Complex Learning Theory (David & Sumara, 2003) which conceptualised learning as an ‘interactive and interpretive process’, such team talks allow players to share their experiences through discussion thereby achieving consensus and empathy through listening to others. To transfer this concept into practice I adopted an adapted version of Grehaigne et al. (2005)’s ‘debate of ideas’ format, this was adopted within a competitive game of 4x20 minute quarters which provided 3 ‘team talks’ for the players. For each quarter I nominated a ‘player coach’ to facilitate discussion around the questions provided…

Question 1: What are the strengths of the other team?

Discussion Points: They play with a lot of width and move the ball to the left quickly

Question 2: How can we stop the strengths of the other team?

Discussion Points: We could try and stop the ball going down that side by forcing play onto the right where the players ‘cuts inside’

Question 3: How will we know that this strategy has worked?

Discussion Points: Coach to count how many times the ball goes to the left-hand side, no crosses from the left-hand side

One issue with this format identified was that 2 players dominated the discussion, to negate this a rule was included that whoever was ‘holding the ball’ was permitted to speak. With a 30 second timer.

To allow players to feel safe, confident, and comfortable to be creative and independent learners, according to Light (2017) it is the role of the coach to build a supportive environment to facilitate this. As a coach within an elite premier league academy there is a culture of ‘elitism’ within youth football where players are often expected to be ‘exceptional’ with the narrative of ‘mini adults’ perpetuated from a young age. This often facilitates a ‘binary’ view for players of success and failure. Which can undoubtedly lead to decreased confidence and creativity to try (Light, 2017). I aim to reconceptualise this communicating to players that ‘mistakes are a part of learning’, in accordance with Light (2017)’s concept of manageability in which players require coaches to frame challenges as both manageable and rewarding. I adopt this through ‘hidden challenge’ in accordance with Launder’s (2001) action fantasy games by implementing a scoring system for training and in-game challenges. For example, challenges that are of increased difficulty, will result in a higher score being given if completed to encourage persistence and motivation.

Conclusion

In conclusion I have attempted to provide a real-world example of how in the day-to-day aspects of youth coaching I have aimed to implement game sense pedagogy within my practice. If anyone has any further questions, I would be more than happy to answer them via email or twitter.

Thanks, and happy coaching!

Ross

den Duyn, N. (1997). Game Sense: Developing thinking players. Canberra: Australian Sports Commission

Dewey, J. (1916/97). Democracy in education. New York: Free Press

Davis, B., & Sumara, D. (2003). Why aren’t they getting this? Working through the regressive myths of constructivist pedagogy. Teaching Education, 14(2), 123–140.

Light, R. L. (2013). Game Sense: Pedagogy for performance, participation and enjoyment. London: Routledge.

Launder, A. G. (2001). Play practice: The games approach to teaching and coaching sports. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Harvey, S., & Light, R. L. (2015). Questioning for learning in game-based approaches to teaching and coaching. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 6(2), 175–190

Kracl, C. L. (2012). Review or true? Using higher-level thinking questions in social studies instruction. The Social Studies, 103, 57–60.

Gréhaigne, J.-F., Richard, J.-F., & Griffin, L. L. (2005). Teaching and learning team sports and games. New York, NY: RoutledgeFalmer

Light, R. L., & Harvey, S. (2017). Positive Pedagogy for sport coaching. Sport, Education and Society, 22(2), 271–287