Lecturer IV, State University of New York at Cortland, Cortland, NY, USA

E-mail: [email protected]

Twitter/X: @cortlandSportEd

Substack: https://thefutureofphysicaleducation.substack.com/

Upcoming Presentation (8th International Conference on Games-Based Teaching and Coaching, Aukland, NZ): Inspiring Active Learners Through Tactical Questioning

Tactical questions drive TGfU and similar Game-Based instructional models and help students move from physical participant to active learner and, ideally, to literate tactician. If phrased and delivered well and connected to the major tactical concepts of the lesson, tactical questions help students comprehend strategies and apply them to mature forms of the game. If the goal is to create students who understand how to play the game, the quality of the overall Game-Based lesson, and the tactical questions throughout the lesson, are paramount (Mitchell, Oslin, and Griffin, 2013).

When I observe practitioners and physical education teacher education (PETE) candidates, the quality of the tactical questions varies greatly. This is often a limiting factor to PETE candidate comprehension of the model initially, and application of the model after some opportunity to practice using it. When new to the TGfU model, teachers in the classroom often struggle with creating appropriate questions. Even veteran teachers who have used Game-Based Approaches to teaching sometimes lack the tactical understanding, planning, or commitment to develop open-ended, well-phrased, and relevant tactical questions.

Theoretical Background

The Spectrum of Teaching Styles (STS), created by Muska Mosston in 1966, was a groundbreaking approach to learning in physical education. Described by Mosston as “a framework of options in the relationships between teacher and learner” the STS includes eleven interconnected teaching methods, that shift from teacher-centered (Style A: Command Style) to learner-centered (Style K: Self-Teaching) (Zeng and Gao, 2012).

While teaching methodologies have evolved over the years, the STS remains influential in the physical education world. Related to the tactical questions introduced above, the guided discovery style (Style F in the STS) “is characterized by creating a logical and sequential series of questions that lead the learners to discover a predetermined response. Simply put, the teacher uses questions to guide the learners towards a specific solution” (Kiikka, 2021).

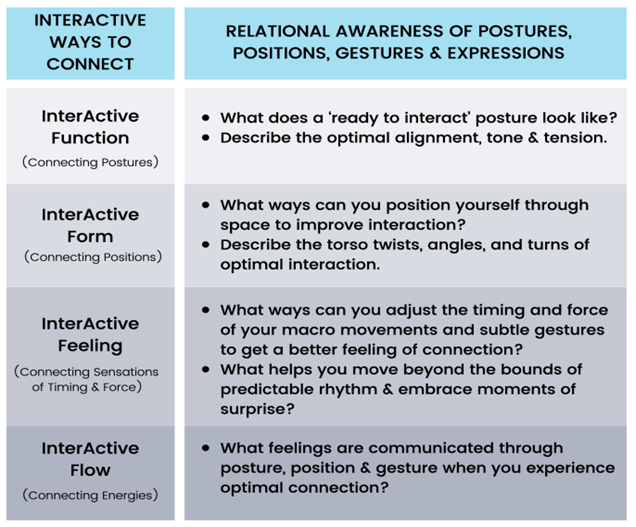

These tactical questions share some critical characteristics of the guided discovery style. In particular, the teacher or coach must have a tactical focus and major tactical concepts that are to be developed in the lesson. The game forms and small-sided games should be designed to create a tactical problem for the learners to solve. In turn, well-phrased tactical questions should lead students to answers that develop responses related to the tactical outcomes desired in the lesson. Further, the teacher must deliver the questions in a way that allows students the opportunity to think, sometimes collaborate, and share answers. The teacher must listen, be patient, avoid answering the questions themselves, and provide relevant feedback that reinforces tactical understanding.

Planning and Implementation

With the aim of improving PETE candidates’ understanding of how to create and deliver well-phrased tactical questions in a seven-week TGfU unit (2 meeting hours per week, including 3 meeting hours of micro-teaching as a culminating activity), a lesson was implemented to focus specifically on practicing creating and delivering tactical questions, then receiving immediate feedback. After modelling six TGfU lessons with PETE candidates participating in a hands-on gymnasium setting, the seventh lesson was designed as follows:

The PETE candidates worked with the professor to develop a clear tactical lesson focus in a team handball unit (example: Zone Defense). Major concepts that support the focus were discussed and listed (example: shifting as a group, when/how to pressure the ball (first defender concepts), team shape, compaction, communication). After these tactical concepts were decided, the professor guided the class to create a game form (example: 6 v 6 defending a modified goal with a “D-zone” (goal area), with the offense required to make a minimum of four passes before shooting. Teams rotated roles after three repetitions, with the game restarted with a pass from the defense to the offense at every dead ball.)

After a brief demonstration of the task, PETE candidates practiced in the game form for 7-10 minutes. At the end of the game form practice, they remained in their teams, and each team was provided with a Question Help Sheet. This Question Help Sheet includes characteristics of a well-phrased tactical question and prompts to help create quality questions. These prompts are specifically the beginning of a given question (examples: “Now that you…?;” “Describe…?”).

Once given the Help Sheet, each small group was assigned the beginning of a question they had to use to ask the rest of the class about their tactical approach in the game form. While PETE candidates read the sheet, the professor stopped briefly at each group to check for understanding and to encourage PETE candidates to think about the tactical responses they expected to get, and how to guide students to those responses.

After about 5 – 7 minutes, groups took turns having a spokesperson, who acted as the teacher. The ‘teacher’ asked the class their tactical question and, after some interaction between the “teacher” and the “students,” the professor provided immediate feedback to the entire class. The class ended with a debrief that allowed teacher candidates to ask any remaining questions about the lesson and how to implement the tactical questioning.

The most common areas that needed improvement are described below:

- Give More Thinking Time/Rephrase the Question

- Relate it to the Stated Lesson Tactical Focus

- Phrase it so it is Open-Ended

- Frame it in the Positive (i.e., How did they solve the problem, not how didn’t they?)

- Bring out the “How” (get students to expand on brief or vague responses)

- Get, do not Give Answers

- Be Good on Your Feet: Listen and Follow-Up

Outcomes

The goal of this lesson was to develop PETE candidates’ understanding of how to phrase and deliver tactical questions in a TGfU or similar Game-Based Approach. Student feedback and performance in a later micro teaching indicated this exercise helped them move from a basic understanding to a more refined understanding with a greater ability to connect the questions to the lesson tactics. While discussion with students was informal, several students stated the timing of the lesson described above was immensely helpful in their progress. This exercise of having 6 lessons to learn TGfU from a student’s perspective, then breaking out of that point of view and into the role of a teacher, helped reinforce the purpose of the questions and how to connect them to tactics learned in the lesson.

It is notable that the timing of this lesson aligns with the introduction of directions for a micro teaching that the PETE candidates will deliver approximately three weeks later. This allowed PETE candidates to create a lesson, including listing questions with potential answers. After receiving lesson feedback, PETE candidates were given the opportunity to revise the lesson before delivering a 7-minute micro teaching where they delivered only a game form and were required to incorporate tactical questioning.

During the debriefs at the end of each of the three micro teaching days, students indicated the following key points that were critical to their development and understanding of Game-Based Approaches to teaching, and specifically to their ability to create and deliver appropriate tactical questions:

- The sequencing of the three weeks of hands-on learning followed by the critical timing of the question development lesson embedded student learning.

- The tactical questions lesson and the specific and timely critique of their questioning immediately upon completion of delivery enabled them to move to a higher level of competence.

- The feedback on their lesson plans contributed to them feeling more confident by the time they taught.

- Learning from peers and seeing a variety of teaching styles and “new voices” during the micro teaching itself supported their development.

- Debriefs at the end of each of the three micro teaching days were described as “the last piece of the puzzle” in building all the learning connections. Most students felt they had a strong foundation and suggested they had the self-efficacy to use Game-Based Approaches and tactical questioning in the future.

Future Considerations

- The Question Help Sheet may be of benefit to others, including teachers who are new to teaching Game-Based Approaches.

- Practicing delivery of the questions and being critiqued by a more experienced practitioner is valuable for students and teachers.

- It is prudent to implement TGfU in sports one is confident in teaching, as a competent level of tactical understanding is necessary to develop effective questions.

- Professional development settings may be helpful to developing teachers and coaches tactical questioning skills.

- Formal research is required.

Bunker, D., & Thorpe, R. (1982). A model for the teaching of games in secondary schools. Bulletin of Physical Education, 18(1), 5–8

Kiikka, Daniel. (2021). The Spectrum of Teaching Styles: The Guided Discovery Style (f). The Sports Edu. https://thesportsedu.com/the-spectrum-of-teaching-styles-summary/

Mitchell, S. A., Oslin, J. L., Griffin, L. L. (2013). Teaching Sport Concepts and Skills: A Tactical Games Approach for Ages 7 to 18. United Kingdom: Human Kinetics.

Mosston, M. & Ashworth, S. (2008) Teaching Physical Education. 1st Online Edition.

Rink, J. (2005). Teaching physical education for learning. McGraw-Hill Education.

Zeng, Z. H., & Gao, Q. (2012). Teaching Physical Education Using the Spectrum of Teaching Style: Introduction to Mosston’s Spectrum of Teaching Style. China School Physical Education; Vol.2012-01, pp. 65-68.