By Dr Greg Forrest

Senior Lecturer and Academic Program Director of Health, Physical Education and Sport Studies at University of Wollongong.

Email: [email protected]

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/grammarofgames/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/greg-forrest-53a497b/

Originally posted in our Guest Blogs- January 2020

Senior Lecturer and Academic Program Director of Health, Physical Education and Sport Studies at University of Wollongong.

Email: [email protected]

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/grammarofgames/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/greg-forrest-53a497b/

Originally posted in our Guest Blogs- January 2020

Greg has been a Physical Educator for 35 years, in schools, sporting environments and for the last 13 years lecturing and researching in games and sports, PE and Sport at UOW. The Grammar of Games emerged from his doctoral study into how undergraduate PE teachers from a variety of movement backgrounds understood and used GBA. It is the basis of movement courses in for PE and Sport Studies at UOW, where undergraduates are drawn from the wide range of sports and movement experiences available in the community. Greg has worked for a number of years with community-based sports and with beginners in sporting teams.

The playing, teaching and coaching of games and sports has been integral to engagement in movement in adult life. For many of us, especially those reading this blog, the most meaningful way to develop the skills to engage is through the use of Game Based Approaches (GBA). However, despite logical and persuasive arguments as to the value of the GBA in games and sports, uptake has been inconsistent and there has been consistent resistance from participants and practitioners to adopt the pedagogies. Simply put, transfer of learning has been uncertain or has not occurred in GBA. Therefore, this article will use the transfer lens to examine games and sports and suggest a new approach they may enhance ToL in games and sports.

Transfer of Learning (ToL) is typically seen as the use of understandings from one learning experience in another. It is a foundational expectation of PE, where the very purpose of our discipline requires transfer of understanding into lifelong engagement in movement. While many reasons have been given for GBA development, from a ToL perspective, developing movement skills simply did not transfer to game play understanding, especially for those who were not experienced in the game or sport selected. On the other hand, it was posited that GBA engaged learners in authentic, progressive, game play and, with supporting divergent questioning, students could improve game play understanding. To put this simply, advocates argued that by using a GBA there would be enhanced ToL for more students.

While much attention has been devoted to exploring the use of GBA and the development of the various aspects of the pedagogies, as evidenced by the wide variety of excellent posts in the TGfU blog, there has been limited exploration of GBA from a ToL perspective. To do so is a worthwhile process, especially considering the explicit lack of evidence of ToL in games and sports, PE and Sport. Areas of concerns with ToL identified in other education disciplines provide an interesting viewpoint, especially as some concerns can be directly connected to GBA use or lack of use. These inhibitors of ToL can be summarised as follows:

When GBA are viewed from this perspective, a strong case can be made that GBA may provide compelling arguments but may be no more successful at ensuring ToL than the traditional approach, despite compelling arguments and best intentions. The points above may also provide reasons for inconsistent uptake and resistance in the PE community.

So, if a strong case can be made for potentially poor ToL, what is the starting point to addressing ToL issues? It may not actually begin with addressing pedagogy, which has been the focus of research and professional learning in PE. For me, it is interesting that advocates of GBA provided the initial way forward by arguing that strategy and tactics and decision making are key concepts in game play understanding. The grouping of sports into game categories also began to address recognised issues with the limitations with time, connecting sports together based on common concepts. However, the focus then shifted to pedagogical solutions which, from a ToL perspective, did not address the ‘elephant in the room’, that is the traditional perspective that Games and Sports operates as one of five /six, separate movement disciplines and is separate to the other areas. While understandable because the perspective was understanding games and sports, it immediately lost the ToL potential. After all, are all three concepts not important in these other PE disciplines?

Since we have come this far, what is the next step? This may be considered a heretical question BUT what if the traditional divisions of PE actually inhibit ToL, make it difficult, if not impossible for ToL to occur. Our learners come from all different movement backgrounds, but the disciplines create disconnected contexts that need to be learnt and understood, the very thing game categories tried to address.

So, what if we group all of these together under ‘Games and Movement Experiences’, treat them all as contexts where concepts interact organically with each other? How would this look for games and sports? It would mean that the concepts are not the sports of the disciplines but the underlying factors or concepts that underpin all of the game and movement contexts. What would such an approach look like?

Welcome to the Grammar of Games.

The ‘Grammar of Games’ identifies these interacting concepts and builds on developing a deep understanding of their relationship with each other in all games / movement contexts. It is an alternative approach to teaching and learning that originated in the games and sports field. The approach aims to improve understanding of all games and sports by attempting to address issues with ToL. Just as grammar provides the tools to understand the signs and symbols of language, the Grammar of Games aims to give meaning to movement experiences through deep understanding of the four ‘grammatical’ concepts that underpin and give meaning to all games or movement contexts.

The Grammar of Games does not necessarily draw upon new knowledge but builds upon the progress made in PE, especially in the GBA field but it perceives it in a different way. The Traditional Approach argued Movement Skill was the foundational concept that was transferable, GBA argued Strategy and Tactics, Decision Making were equally important for the ToL to occur. Based on my own extensive experiences, I have taken the liberty of adding Communication and Concentration as the fourth concept, as I believe it is the most neglected area of game / movement context understanding, especially for beginners. It also draws upon more thematic approaches in GBA that, of all GBA, have demonstrated some evidence of ToL (see Mitchell and Oslin, 1999). And the work of Gréhaigne, Richard and Griffin (2005), who have provided in depth content knowledge in the concepts of strategy and tactics and decision making but only applied this in FTI games and sports.

The playing, teaching and coaching of games and sports has been integral to engagement in movement in adult life. For many of us, especially those reading this blog, the most meaningful way to develop the skills to engage is through the use of Game Based Approaches (GBA). However, despite logical and persuasive arguments as to the value of the GBA in games and sports, uptake has been inconsistent and there has been consistent resistance from participants and practitioners to adopt the pedagogies. Simply put, transfer of learning has been uncertain or has not occurred in GBA. Therefore, this article will use the transfer lens to examine games and sports and suggest a new approach they may enhance ToL in games and sports.

Transfer of Learning (ToL) is typically seen as the use of understandings from one learning experience in another. It is a foundational expectation of PE, where the very purpose of our discipline requires transfer of understanding into lifelong engagement in movement. While many reasons have been given for GBA development, from a ToL perspective, developing movement skills simply did not transfer to game play understanding, especially for those who were not experienced in the game or sport selected. On the other hand, it was posited that GBA engaged learners in authentic, progressive, game play and, with supporting divergent questioning, students could improve game play understanding. To put this simply, advocates argued that by using a GBA there would be enhanced ToL for more students.

While much attention has been devoted to exploring the use of GBA and the development of the various aspects of the pedagogies, as evidenced by the wide variety of excellent posts in the TGfU blog, there has been limited exploration of GBA from a ToL perspective. To do so is a worthwhile process, especially considering the explicit lack of evidence of ToL in games and sports, PE and Sport. Areas of concerns with ToL identified in other education disciplines provide an interesting viewpoint, especially as some concerns can be directly connected to GBA use or lack of use. These inhibitors of ToL can be summarised as follows:

- There is an inadequate amount of time in lessons, units, sessions to develop mastery in key concepts required to facilitate the transfer of these concepts into different contexts;

- Activities assumed to be authentic and relevant by educators are not viewed in the same way by the learner;

- There is a lack of clarity about what is to be transferred, leading to an over optimistic expectation of ToL, noted by Perkins and Salomon (1992) as the Bo Peep or ‘leave it alone’ teaching strategy and

- There is an assumption by educators that learners will be motivated to engage with the transfer process, which requires them to be active agents who are willing to challenge old beliefs and adopt new ones.

When GBA are viewed from this perspective, a strong case can be made that GBA may provide compelling arguments but may be no more successful at ensuring ToL than the traditional approach, despite compelling arguments and best intentions. The points above may also provide reasons for inconsistent uptake and resistance in the PE community.

So, if a strong case can be made for potentially poor ToL, what is the starting point to addressing ToL issues? It may not actually begin with addressing pedagogy, which has been the focus of research and professional learning in PE. For me, it is interesting that advocates of GBA provided the initial way forward by arguing that strategy and tactics and decision making are key concepts in game play understanding. The grouping of sports into game categories also began to address recognised issues with the limitations with time, connecting sports together based on common concepts. However, the focus then shifted to pedagogical solutions which, from a ToL perspective, did not address the ‘elephant in the room’, that is the traditional perspective that Games and Sports operates as one of five /six, separate movement disciplines and is separate to the other areas. While understandable because the perspective was understanding games and sports, it immediately lost the ToL potential. After all, are all three concepts not important in these other PE disciplines?

Since we have come this far, what is the next step? This may be considered a heretical question BUT what if the traditional divisions of PE actually inhibit ToL, make it difficult, if not impossible for ToL to occur. Our learners come from all different movement backgrounds, but the disciplines create disconnected contexts that need to be learnt and understood, the very thing game categories tried to address.

So, what if we group all of these together under ‘Games and Movement Experiences’, treat them all as contexts where concepts interact organically with each other? How would this look for games and sports? It would mean that the concepts are not the sports of the disciplines but the underlying factors or concepts that underpin all of the game and movement contexts. What would such an approach look like?

Welcome to the Grammar of Games.

The ‘Grammar of Games’ identifies these interacting concepts and builds on developing a deep understanding of their relationship with each other in all games / movement contexts. It is an alternative approach to teaching and learning that originated in the games and sports field. The approach aims to improve understanding of all games and sports by attempting to address issues with ToL. Just as grammar provides the tools to understand the signs and symbols of language, the Grammar of Games aims to give meaning to movement experiences through deep understanding of the four ‘grammatical’ concepts that underpin and give meaning to all games or movement contexts.

The Grammar of Games does not necessarily draw upon new knowledge but builds upon the progress made in PE, especially in the GBA field but it perceives it in a different way. The Traditional Approach argued Movement Skill was the foundational concept that was transferable, GBA argued Strategy and Tactics, Decision Making were equally important for the ToL to occur. Based on my own extensive experiences, I have taken the liberty of adding Communication and Concentration as the fourth concept, as I believe it is the most neglected area of game / movement context understanding, especially for beginners. It also draws upon more thematic approaches in GBA that, of all GBA, have demonstrated some evidence of ToL (see Mitchell and Oslin, 1999). And the work of Gréhaigne, Richard and Griffin (2005), who have provided in depth content knowledge in the concepts of strategy and tactics and decision making but only applied this in FTI games and sports.

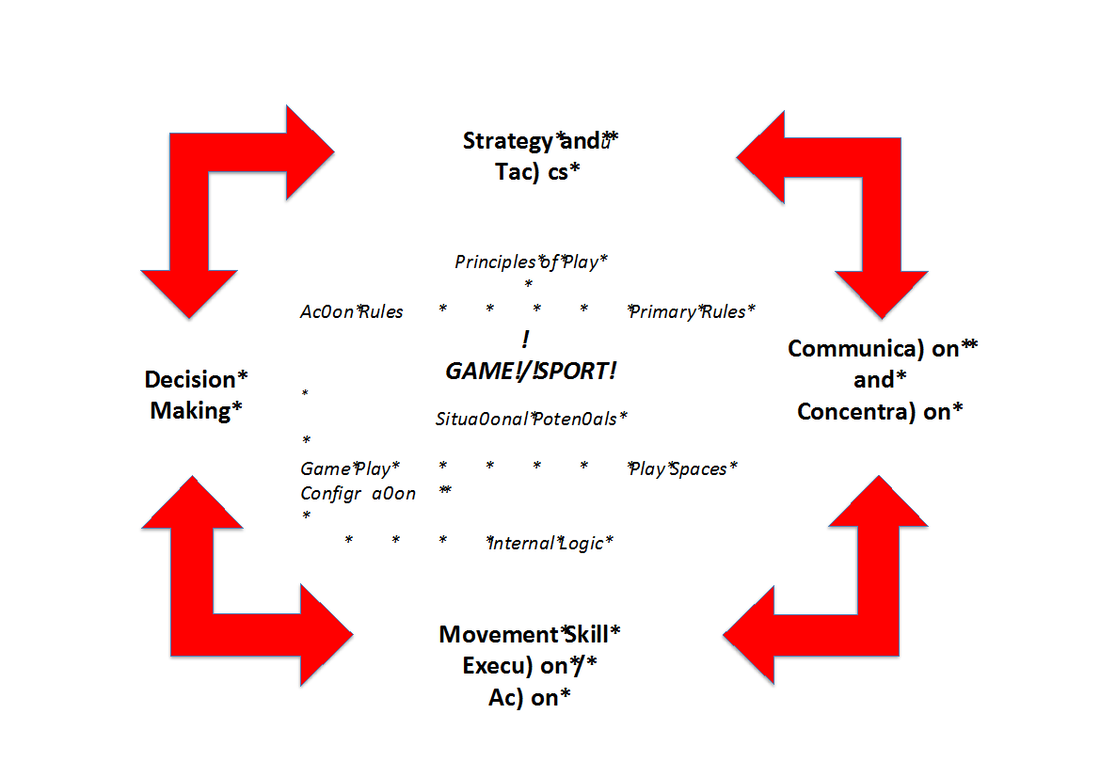

Figure 1: The Grammar of Games (Forrest, 2015)

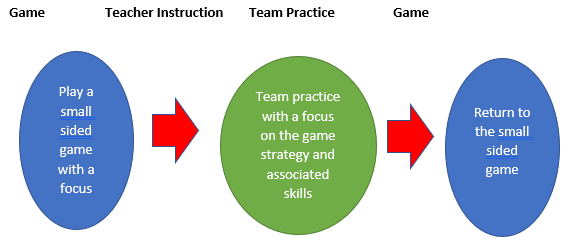

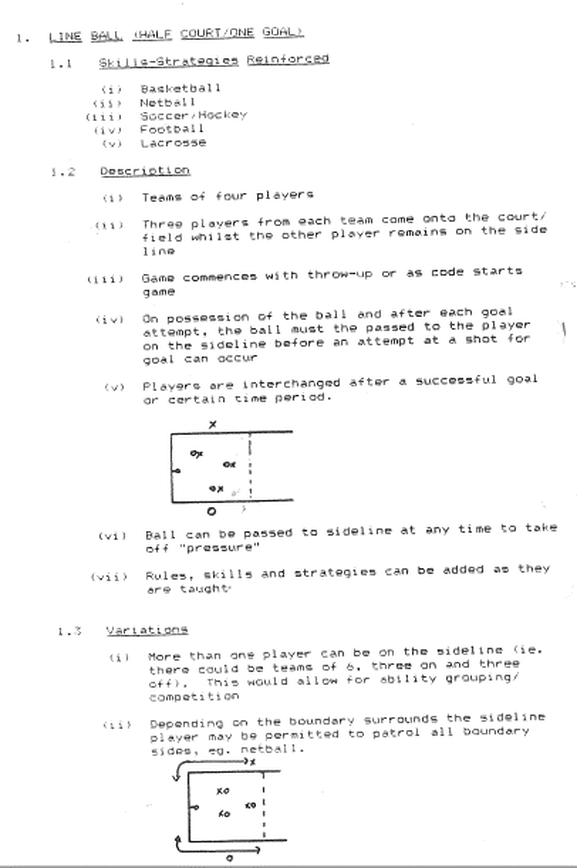

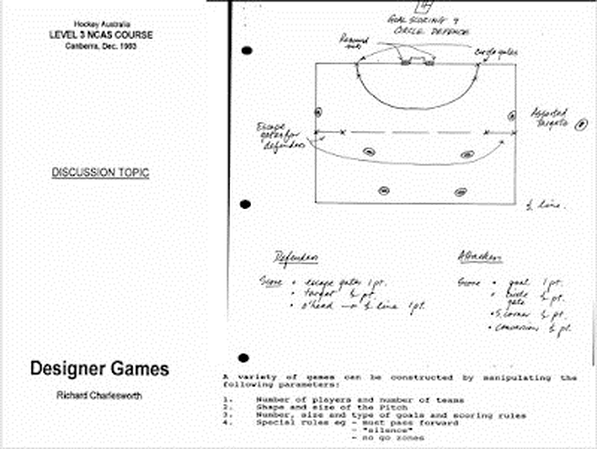

So how does it work? Well, a game, sport or movement experience can be placed in the centre of the model (and if we want to connect with all students, any experience is valid). Every experience is founded in principles, action and primary rules, configurations and spaces. Play action can be a product of the plans we make beforehand (strategy) or during play (tactics), is based on decisions at a team or individual level, which in turn determined by movement skills, which then influence what we communicate about and concentrate on. However, each concept interacts with the others organically as play evolves and has an influence on the other three. For example, any tactical change will necessitate an alteration in what we concentrate on and what decisions we make and what movement skill adaptations we make. As we are dealing constantly with interaction, learning experiences are generally based in game play and the approach can be used at a more generic game level or in a specific sport context. However, the game play aspect positions the Grammar of Games firmly in the GBA family with the concepts providing both the basis of observation and questions and the frame in which to make game progressions. Thus, if the educator wishes to focus on Tactical Changes to strategy, he/she can progress the game by changing a parameter (primary rule) that directly impacts on tactics in play, all the while knowing that there may be potential changes to the other three concepts.

Using the Grammar of Games allows us to change our perspective (as educators and learners) in how we understand games and sport as movement experiences. By developing a deep understanding of the grammatical concepts and their relationship in play, players, students, coaches and teachers can have a greater opportunity to connect with each other through the activities used, regardless of their background. This means that it does not matter whether we teach, assess or program water polo, football, rock climbing, snowboard cross, hammer throw, diving, swimming, surfing, lacrosse, lawn bowls, cycling, show jumping or have students who engage in chess, cards or video games*. Each is simply a context where these four concepts interact.

There are also a range of advantages to such an approach in relation to ToL. They include;

Using the Grammar of Games as the foundation of understanding in movement experiences and educational programs gives educators the capacity to potentially address the issues of ToL. By changing perspective on what are key concepts and contexts in relation to what we wish all students to learn and understand in games and movement experiences, we can have the potential to improve. While it cannot necessarily motivate people to change habits or willingly embrace the process required to enhance ToL, it gives us a unique opportunity to connect our learners and educators in a meaningful fashion and provide potential for GBA to meet some of the ToL challenges.

References

Forrest, G. (2015). New approach for games and sports teaching. Research and Innovation: Issue One. University of Wollongong.

Gréhaigne. J R, Richard, J.F. and Griffin. (2005) Teaching & Learning Team Sports and Games. Routledge Falmer, New York.

Mitchell, S. A. and Oslin, J. L. (1999) ‘An Investigation of Tactical Transfer in Net Games’, European Journal of Physical Education 4: 162–72.

Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (1992). Transfer of learning. International Encyclopedia of Education, 2, 6452-6457.

Using the Grammar of Games allows us to change our perspective (as educators and learners) in how we understand games and sport as movement experiences. By developing a deep understanding of the grammatical concepts and their relationship in play, players, students, coaches and teachers can have a greater opportunity to connect with each other through the activities used, regardless of their background. This means that it does not matter whether we teach, assess or program water polo, football, rock climbing, snowboard cross, hammer throw, diving, swimming, surfing, lacrosse, lawn bowls, cycling, show jumping or have students who engage in chess, cards or video games*. Each is simply a context where these four concepts interact.

There are also a range of advantages to such an approach in relation to ToL. They include;

- An explicit connection with all movement experiences via the concepts provides the potential for authenticity with all students in our classes, irrespective of their movement background and clearly;

- Content knowledge is based on four concepts, addressing the time factor in developing depth of understanding, allowing for more in depth of understanding and connection as activities to move from the simple (generic games) to more complex representations (game categories, disciplines, specific sports);

- Assessment is based on the for concepts and how they interrelate in game play, regardless of the context, rather than a sport or category or discipline. Thus, students can demonstrate their knowledge and understanding of the concept across a range of discipline contexts and teachers can compare different contexts more effectively. The approach also removes the bias of assessing those who have learnt sports in different environments by requiring them to be flexible with the knowledge understanding and application of concepts, demonstrating true game play understanding;

- The potential to improve teacher capacity to use educationally sound approaches such as GBA more meaningfully. An understanding of the four concepts provides an entry level into all movement experiences, removing the barrier of what we know based on the category or discipline and examining games and movement experiences based on how the concepts interact in the game in front of us. The concepts are also directly derived from GBA so by deepening our knowledge in these concepts from a general perspective, we have a greater capacity to meet the important markers that make GBA such a valuable pedagogy, such as game progression and questioning.

Using the Grammar of Games as the foundation of understanding in movement experiences and educational programs gives educators the capacity to potentially address the issues of ToL. By changing perspective on what are key concepts and contexts in relation to what we wish all students to learn and understand in games and movement experiences, we can have the potential to improve. While it cannot necessarily motivate people to change habits or willingly embrace the process required to enhance ToL, it gives us a unique opportunity to connect our learners and educators in a meaningful fashion and provide potential for GBA to meet some of the ToL challenges.

References

Forrest, G. (2015). New approach for games and sports teaching. Research and Innovation: Issue One. University of Wollongong.

Gréhaigne. J R, Richard, J.F. and Griffin. (2005) Teaching & Learning Team Sports and Games. Routledge Falmer, New York.

Mitchell, S. A. and Oslin, J. L. (1999) ‘An Investigation of Tactical Transfer in Net Games’, European Journal of Physical Education 4: 162–72.

Perkins, D. N., & Salomon, G. (1992). Transfer of learning. International Encyclopedia of Education, 2, 6452-6457.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed